Hobbies

1st November 2017

White-Tailed Eagles

1st November 2017Peregrine Falcons

Some say they can fly at up to 240mph. Some say they can decapitate their prey on impact. Some say they can hunt at night. All we know is, they're called peregrine falcons.

Say "Hello" To The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)

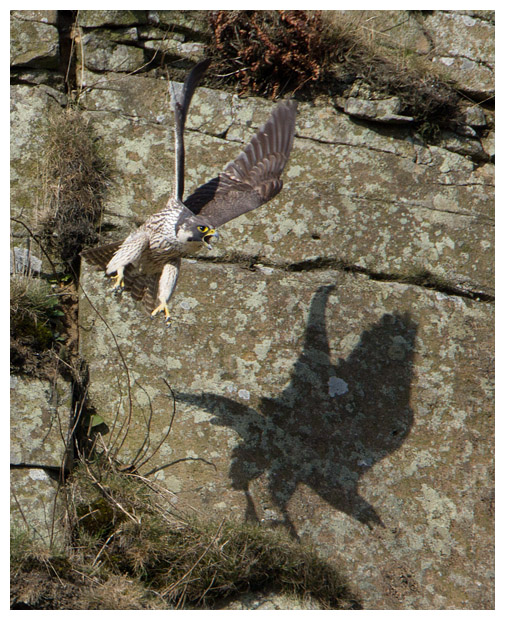

Meet the fastest animal on the planet. Recorded at speeds in excess of 200mph when diving for prey, this falcon is truly one of the most spectacular and breathtaking hunters to watch.

Appearance

Built for speed, the peregrine falcon has a stocky, muscular physique, with a bulky chest. In flight, when not pursuing prey they tend to fly in a straight line flapping all the while, unlike say sparrowhawks that have a flap-flap-glide ... flap-flap-glide pattern. Peregrines often make use of thermals to circle up to great heights to spot prey from, and hence be able to build up enough speed for a dive.

When seen from below, they have a finely barred body and a white ring just below the distinctive dark hood on the head. From above the bird is a dark, slate grey colour. Feet are large and yellow. And the beak is also yellow with a dark tip.

As with most raptors, the female is significantly larger than the male (tercel).

Juveniles are more heavily marked and have a browner tint to them. And their beaks are greyish-blue.

I find that I often hear peregrines before seeing them, as they have a distinctive cry, sort of a cross between a herring gull and a kestrel; it's a haunting call. They make a number of different cries, but once you know what one sounds like, you instantly connect when you hear one. And this can be very handy when trying to spot them, given their speed and preference for high vantage points.

Hunting

The element of surprise is key to the peregrine, and it has mastered the art of diving at incredible speeds down to intercept prey in mid-air. The starting point might simply be from a lofty perch, perhaps the top of a cliff or tall building, or from high in the sky as the falcon circles above the prey.

Once spotted, the peregrine goes into a dive and hurtles down towards the unsuspecting bird, flying head-first and flapping its powerful wings to increase speed. At the last second, it brings its feet forwards and slams into the prey flat out, stunning it on impact. If this doesn't kill the prey, it will use its specially evolved sharp beak to bite the back of the neck of the caught bird to kill it. This can be done in flight or when the peregrine has landed shortly afterwards.

If the prey was missed in the dive, the peregrine will often pursue the bird to catch it from behind. This is fine for the peregrine if it is faster in straight line flight, but some birds such as pigeons can fly faster horizontally than the peregrine, so will actually outrun it.

They will also sometimes force their prey to ditch into the water below - something I have seen done repeatedly when a peregrine was chasing terns at a colony on Anglesey one year. I believe the intention is to then pluck the exhausted bird from the surface. Alas in the instance of the terns, the prey was full of energy so wouldn't stay still long enough, and the hunter was a juvenile and lacked the necessary skills to complete the action. It gave up eventually and sat nearby, on a hillside, looking rather annoyed!

Tern ditches into the water to escape the peregrine

Once the kill has been made, the peregrine will sit for several minutes carefully plucking the feathers from it, before eating. The birds I have watched over the years definitely have preferred dining spots, with a carpet of plucked feathers nearby, clearly showing this.

As for being able to hunt at night - this is only performed in towns and cities, and only where the street lighting allows the peregrines to see the prey flying past (and also see enough not to crash into anything whilst chasing it). Birds such a waders that fly at night to avoid such predators have become targets because they have pale underparts that reflect the street lighting, and make them obvious to any peregrine watching the area.

Prey items are varied, from small birds such as finches and snipe, right up to much larger species, such as gulls and even pheasants. Pigeons and wildfowl are favourites though.

Breeding

Early in Spring, peregrines may start to pair up, and this may involve battling for a mate and also for a suitable territory in which to breed. I have been fortunate to witness three falcons battling for a partner and if anything this was more spectacular than seeing them hunt.

Launching off from the cliffs, they would fly off to gain height, and then go into a dive, skimming the ground at break-neck speeds before flying up the cliff-face once more to engage their rival. I happened to be standing below the cliffs watching this once, and had the falcon fly past me so closely that I could hear the fizz from the air passing over it. That was a pretty special moment!

Battles may involve simple mid-air chases, or can see rivals locking talons, and spinning through the sky.

Once paired with any rivals chased off, the peregrines find a suitable nesting spot to lay their eggs. On cliff faces this tends to be a sheltered spot, perhaps a ledge or crevice. And on buildings, they choose something similar - many taller buildings these days actually have peregrine platforms added to them to encourage them to nest.

Whilst sitting on the eggs, the male will often bring in prey for the female, who will briefly leave the nest to collect and eat the food, before returning once more. The nest area is usually very quiet during this time. Typically two or three eggs will be laid.

After hatching, the nest becomes noisier, though the chicks only beg for food when one of the adults is nearby. At other times they know to be quiet, so as not to attract the attention of anything that might prey upon them. That said, even when the adults are off hunting, it is like they have a sixth sense of when something is a threat, and return almost instantly to chase off whatever might have ventured too close to the nest. I assume one of the pair keeps an eye on the nest site at all times, while the other is doing the hunting.

Normally corvids are the main concern, ravens in particular, but I have seen buzzards, kestrels, magpies and carrion crows all chased off, and even other peregrines at times.

Having caught something, one of the adults tends to pluck it for a while, then eat some, before taking it to the nest where it is pulled to pieces, and fed in tiny morcels to the hungry chicks.

Peregrine nestlings being fed

Fledging

When the chicks have grown too big for the nest area, they will flap their wings to build enough muscle to be able to fly. They can be seen furiously flapping and just about getting airborne, for a few days before they actually risk leaving for real, and even then, they return to perch up near the nest if not beside it again, as this is where the adults still bring their food.

Gradually they find new perches to rest upon between test flights, and the adults will bring prey to these new spots, leaving it to be plucked and eaten by the fledglings, rather than helping. They seem to learn this very quickly - in a matter of days.

Simply flying is the first step, but peregrines need to be able hunt on the wing, so once airborne, the chicks (if there are two or more) will begin practising actions in mid-air to aid them in hunting later in their lives, such as catching prey and handling it on the wing.

I have seen young peregrines lock talons with each other as they soared overhead, only releasing after they crash-landed on a hillside, thankfully at a speed slow enough not to cause any damage to them. I guess they have to be tough to withstand the stresses of impact when connecting with prey at such speeds.

They seem to have speedy reactions naturally though, as whilst watching one fledgling flying slowly around the hills near its nest, it put up a flock of finches and pipits, and seemed surprised when the flock flew right up at it. Yet it still had the instinct to reach out and catch one of the pipits within its talons! It then returned to the cliff face to kill and eat the unexpected meal, with its sibling perched nearby, begging for a portion of the meal.

This pecking order seems to be common with siblings, with one of the chicks eating first, leaving the other(s) to wait their turn, though I have seen the more dominant one actually feed its siblings once it had finished eating itself.

The family idea can also be seen when the adults don't chase off other peregrines that perch up near the nest area. Perhaps these birds are previous year's chicks grown up, and I have seen these third-party individuals help guard the territory by chasing off threats.

Juveniles sparring in mid-air

Persecution

A sad fact about peregrines is that they eat pigeons, and as such don't see the difference between wild pigeons, and someone's prize-winning racing pigeon. This makes them very unpopular with the pigeon fanciers, and rather than accepting that raptors are a part of the many dangers their pigeons face, such as buildings, large glass windows, domestic cats, wires and traffic, a small minority choose to take the law into their own hands and kill the peregrines.

Poison, usually rodent poison, is a common killer of peregrines, with the pigeon fancier leaving bait (usually one of their own birds) out tethered to the ground near the peregrines' nest site. The bait is laced with the poison. The peregrines take the free meal, eat it, perhaps feed it to their young and all die a horrible, painful death. Job done.

Another recent finding is that some pigeons, called tumblers on account of their habit of tumbling from the sky in short seemingly uncontrolled tumbles, are fitted with sharp hooks behind their feet. It is thought that peregrines can catch these pigeons during one of their tumbles more easily than others. Hence the peregrine catches the pigeon and is injured by the hooks. As with most hunters in the wild, once injured, they can't hunt, and will die of starvation.

I have alas seen first-hand the results of poisoning, when a nest I was watching, and adults I had followed for years were killed by poisoned bait being left near the nest site. Not only did the adults perish, but so did the nestlings. I still feel sad and incredibly angry at this mindless act. Yet these people call themselves "bird lovers", claiming that peregrines (and sparrowhawks, merlins and other bird-eating raptors) are the real criminals here, killing these poor defenceless birds just to eat.

It's called nature. It's part of an ecosystem and it is far more natural than racing pigeons around a country. Peregrines, like the other raptors mentioned take lots of different species of birds, and have a hard job catching anything, inspite of their abilities. They should be marvelled at, not killed.

Photographing Peregrines

Peregrines are on the Schedule 1 list of protected birds, so should not be photographed at a nest site, unless the nest is visible from a public viewing location, or you have the necessary licence to do so. Even then, any photography should be conducted in such a way as to ensure no disturbance is made to the nest at all.

There are also a growing number of public urban peregrine sites now, where the birds roost and nest on tall buildings, and organisations rig cameras to monitor their behaviour. These sites can be great places to stand beside to watch and photograph the birds as they perch up and hunt.

Away from nest sites, and at other times of the year, photographing peregrines is great fun, and the best way to get perched images is to watch the birds to see where they land.

As mentioned above, tell-tale piles of discarded feathers will be a good indicator of where one might perch up to pluck prey. Another might be a lofty vantage point, where the peregrine sits and watches any potential prey fly by.

When flying against the sky they are easier to pick up to focus upon, but flying against a cliff face or building can make tracking them difficult. Here you need to engage the tracking focus mode of your camera, and use perhaps an expanded focus point to enhance your chances of retaining a lock on them as they fly by. Given their speed, it's no surprise to know that they need a fast shutter speed to freeze the action and not yield a blurred image of them. And while they are fast, they do tend to fly in a straight line, unlike hobbies for example, so predicting a line they might fly along is a little easier.

Practice will improve your results, but on a day when things might not be going your way with images, I like to sometimes just stand back from my camera, and simply watch these awesome aerial masters perform their magic in the sky.